Adventures in F# Performance

Apologies to functional programming enthusiasts, what follows is a lot of imperative code. What can I say, it is the array library after all!

After working on an F# SIMD Array library for a while, and learning about some nice bench marking tools for .NET thanks to Jared Hester. I got the idea to try contributing to the F# core libraries myself. I had been poking around in the official Microsoft F# repo because I was modeling my SIMD Library after the core Array library, duplicating all relevant functions in SIMD form. As I got familiar with the code I saw a function I thought I could speed up. Steffen Forkmann pointed me to a blog post of his about how to get started building and contributing to the FSharp language, so I got to work.

Array.filter

This was the first function I thought I could improve, and mostly I was wrong! Array.filter takes an array and a predicate function as its

arguments and applies the function to each element of the array. The resulting array contains only the elements that satisfy the predicate.

The original implementation used a List

let filter f (array: _[]) =

checkNonNull "array" array

let res = List<_>() // ResizeArray

for i = 0 to array.Length - 1 do

let x = array.[i]

if f x then res.Add(x)

res.ToArray()

I tried a few things, and settled on this for a while:

let filter f (array: _[]) =

checkNonNull "array" array

let temp = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked array.Length

let mutable c = 0

for i = 0 to array.Length-1 do

if f array.[i] then

temp.[i] <- true

c <- c + 1

let result = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked c

c <- 0

let mutable i = 0

while c < result.Length do

if temp.[i] then

result.[c] <- array.[i]

c <- c + 1

i <- i + 1

result

This allocates an array of booleans the same length as the input up front, which are usually stored as bytes in .NET. So in the common case, where you have a 32bit or 64bit pointer, int, or float, as your array element, it will allocate no more than 1/8 to 1/4 of your array size in extra data instead of 3x to 4x. Reducing GC pressure is a big win with garbage collected languages so that seemed like a good thing. There are some gotchas though:

- The loops now both have branches in them.

- The branch pattern will sometimes be random, so branch prediction will miss them, which is slow.

- The performance advantage goes negative compared to the original implementation as the size of the array type shrinks.

So in cases where most things are filtered, and the distribution of elements is somewhat random as to whether they get filtered or not, performance was sometimes worse. Performance also differed in 32bit vs 64 bit builds, and on different machines. Benchmarking this was really hard because you have to account for different array type sizes, lengths, different distribution of filtering and amount of filtering. It didn’t always win, and it was hard to decide if it was really better.

Then Asik suggested a solution which ended up being the final answer:

let filter f (array: _[]) =

checkNonNull "array" array

let res = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked array.Length

let mutable count = 0

for x in array do

if f x then

res.[count] <- x

count <- count + 1

Array.subUnchecked 0 count res

This just allocates an entire array of whatever type was input, adds elements into it, and then uses Array.sub which calls fast native code to copy sub sections of arrays into new ones. This was always faster than the original core lib solution, but sometimes allocated more memory. The Microsoft guys considered that a net win, so they took it. The improvement here varied a lot, but was usually around 20% faster. Worst case performance would be with large array types (Like a 16 byte struct) where most elements are likely to get filtered. You might want to roll your own filter if you are doing that. This same optimization was applied to the similar Array.choose function.

UPDATE:

Asik and I have collaborated and got a new filter merged that keeps the speed of the above solution, while reducing allocations by ~30% on average. We did this by implementing a growing array by hand, taking advantage of extra knowledge we have, like that the upper bound for it’s size is array.Length, and some other tricks. Another interesting solution is being proposed by Paul Westcott which uses a bit array. This may reduce allocations yet again while maintaining similar rerformance, pretty cool.

As an aside, if your predicate is a pure function, and a fast function, you can apply the predicate twice to avoid any extra allocations at all. This is very fast for sufficiently simple predicates, like > or < comparisons.

Performance test results for filtering 50% of random doubles on 64bit RyuJit

| Method | Median | StdDev | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Bytes Allocated/Op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoreFilter | 10.7906 ms | 0.2096 ms | 20.00 | - | 314.00 | 3 953 196,34 |

| ArrayFilter | 8.3605 ms | 0.0374 ms | - | - | 329.99 | 3 762 296,97 |

Array.partition

I wasn’t too happy with the filter optimization because I felt like someimtes taking a memory hit wasn’t so great. So I started scanning through the library for other opportunities, and came across Array.partition, which takes an array and a predicate, returning a tuple with two arrays. One array contains every element that was true, the other every element that was false.

let partition f (array: _[]) =

checkNonNull "array" array

let res1 = List<_>() // ResizeArray

let res2 = List<_>() // ResizeArray

for i = 0 to array.Length - 1 do

let x = array.[i]

if f x then res1.Add(x) else res2.Add(x)

res1.ToArray(), res2.ToArray()

I had more respect for the (array backed) List solutions now, after failing to get a clear win by using raw arrays with filter. So I tried to look for something more clever. I realized that one invariant here is that the result will always be the same size as the input. If the input is 100 elements, the output will be 100 elements. So fundamentally, we shouldn’t need to use a data structures that grows. I thought about creating a struct where you could tag each element with a true or false on the first pass, and then copy the results into the two output arrays. But that still wastes array.Length bytes of memory. Then I had a great idea, maybe my best idea! Allocate an array the same size and type as the input, and put all the true elements on the left, and all the false elements on the right! The only memory wasted is an extra int to keep track of where one set ends and the other begins. You then just copy the left side of the array into the first result, and the reverse of the right side of the array into the second result:

let partition f (array: _[]) =

checkNonNull "array" array

let res = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked array.Length

let mutable upCount = 0

let mutable downCount = array.Length-1

for x in array do

if f x then

res.[upCount] <- x

upCount <- upCount + 1

else

res.[downCount] <- x

downCount <- downCount - 1

let res1 = Array.subUnchecked 0 upCount res

let res2 = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked (array.Length - upCount)

downCount <- array.Length-1

for i = 0 to res2.Length-1 do

res2.[i] <- res.[downCount]

downCount <- downCount - 1

res1 , res2

Performance test results for partitioning random int arrays with predicate (fun x -> x % 2 = 0)

| Method | ArrayLength | Median | StdDev | Scaled | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Bytes Allocated/Op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partition | 10 | 180.8758 ns | 16.3650 ns | 1.00 | 0.01 | - | - | 185.22 |

| NewPartition | 10 | 76.6145 ns | 1.2114 ns | 0.42 | 0.01 | - | - | 90.38 |

| Partition | 10000 | 117,268.5175 ns | 1,064.2667 ns | 1.00 | 6.40 | - | - | 99,742.26 |

| NewPartition | 10000 | 79,020.6291 ns | 474.4149 ns | 0.67 | 2.64 | - | - | 43,572.00 |

| Partition | 10000000 | 154,545,402.8213 ns | 3,116,253.3692 ns | 1.00 | - | - | 62.02 | 59,133,643.66 |

| NewPartition | 10000000 | 98,768,489.7225 ns | 726,198.4079 ns | 0.64 | - | - | 34.00 | 29,686,956.03 |

Adventures in IL and Dissasembly

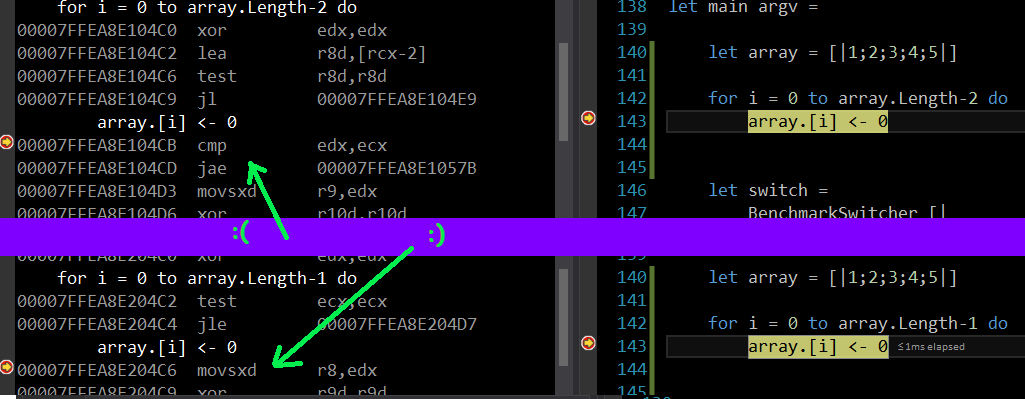

One of the performance drawbacks of most managed/safe languages is that they do array bounds checking. This prevents you from accidentally wandering off the end of an array and over writing memory at random, which is a useful feature. But it comes with a performance cost, as you end up eating some cpu cycles checking array bounds each time through the loop. The .NET JIT will identify Some but not all cases when these bounds checks can be eliminated. You have to take some care to structure your loop just right, or it will be missed. F# added some confusion here since their loops have different syntax than C#, and sometimes compile strangely, or badly. You can peek at the byte code or C# equivalent representation of it with tools like ILSpy For instance this loop:

let len = array.Length

for i = 0 to len-1 do

(* stuff *)

compiles to the C# equivalent of:

int num = len - 1;

if (num >= i)

{

do

{

// stuff

i++;

}

while (i != num + 1);

}

This is madness, maybe some of that madness gets JITted away, but it definitely does cause the array bounds elision to be missed, slowing it down. This was a pattern used in many places in the core Array library, so I just went through and mechanistically replaced them all with the pattern that works:

for i = 0 to array.Length-1 do

(* stuff *)

Which becomes the C# equivalent of:

for (int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++) {

//stuff

AHHHH, much better, and now we get array bounds elision from the JIT too. The impact of this change can be pretty big in some cases, when any functions applied per array element are very simple the array bounds checking makes up a sizeable % of total run time. In other cases it will be a very small impact. Array.map (fun x-> SieveofEratosthenes x) isn’t going to be noticeably better. But it impacted almost all of the functions in the Array module, and I assume (which is dangerous) it would take some overhead out of JITing the IL as well.

If you want to know for sure if the loop is doing what you want, as 32Bit JITs differ from the 64 bit one differ from Mono etc., you will need to view the dissasembly. In Visual Studio you can get it at from Debug -> Windows -> Disassembly while the program is running. Here is an example of code with, and without a bounds check:

Since this process is done in the JIT, you don’t always have control over it. Sometimes you can massage your code to be sure the JIT will do the right thing, but sometimes you can’t. If you get desperate, write the function in C# using an unsafe loop, and call it from F#.

Other loop patterns to beware of in .NET:

- For lops that go from 0 to anything less than the array length, will not get the bounds check elided.

- For loops that go backwards, will not get array bounds checking elided.

- With for loops over arrays in F# that have a stride length of something other than 1, the compiler generates a loop that uses an Enumerator, which is much slower and generates garbage. Use a while loop, or tail recursion instead.

- For loops over arrays that are class members will miss the array bounds elision. Make a function local copy of the array reference first.

- The

for x in arraysyntax in F# works out fine. There may be other performance considerations but a normal for loop is generated and bounds checking is elided.

These things are all true as of 64bit RyuJIT .NET 4.6.2 and F# 4.4.0, some of them are being actively worked on and could improve soon.

Performance test results of bounds check elision from Array.map with mapping function (fun x -> x + 1)

| Method | Length | Median | StdDev | Scaled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | 10 | 17.5030 ns | 0.5275 ns | 1.00 |

| New | 10 | 14.1205 ns | 0.4858 ns | 0.81 |

| Old | 10000 | 10,212.8762 ns | 118.7990 ns | 1.00 |

| New | 10000 | 8,963.2690 ns | 329.8907 ns | 0.88 |

Delving Into Parallel

The Array module has a sub module Parallel. Array.Parallel.map, for instance, will use a Parallel.For loop to multithread your map operation. Scanning through these

I saw Parallel.partition:

let partition predicate (array : 'T[]) =

checkNonNull "array" array

let inputLength = array.Length

let lastInputIndex = inputLength - 1

let isTrue = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked inputLength

Parallel.For(0, inputLength,

fun i -> isTrue.[i] <- predicate array.[i]

) |> ignore

let mutable trueLength = 0

for i in 0 .. lastInputIndex do

if isTrue.[i] then trueLength <- trueLength + 1

let trueResult = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked trueLength

let falseResult = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked (inputLength - trueLength)

let mutable iTrue = 0

let mutable iFalse = 0

for i = 0 to lastInputIndex do

if isTrue.[i] then

trueResult.[iTrue] <- array.[i]

iTrue <- iTrue + 1

else

falseResult.[iFalse] <- array.[i]

iFalse <- iFalse + 1

(trueResult, falseResult)

What stuck out at me here was that they were iterating over the entire isTrue array a second time in order to count up how many true elements

there are. This struck me as fundamentally unnecessary. So I tried creating an accumulation variable above the Parallel.For call, and just incrementing

that within the loop. Nope! You can’t add in parallel like that safely on x86 (or perhaps any architecture?) It worked sometimes but not always. Then I remembered

System.Threading.Interlocked.Increment(Int32), which provides a thread safe way to increment an int. This worked! But then it was just as slow as the

scalar version of the function, since every thread was constantly locking on the increment function. So I

read the documentation. Sometimes this stuff is awful to

read. Func<Int32>? Action<TLocal>? PC LOAD LETTER?!?! But if you go slow and stare at this for a while it will start to make sense. The key info here

is that there is a Parallel.For loop which can internally keep track of an accumulator for you. This will let us track the total number of true

elements without iterating over the array again. So the new solution becomes:

let partition predicate (array : 'T[]) =

checkNonNull "array" array

let inputLength = array.Length

let isTrue = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked inputLength

let mutable trueLength = 0

Parallel.For(0,

inputLength,

(fun () -> 0),

(fun i _ trueCount ->

if predicate array.[i] then

isTrue.[i] <- true

trueCount + 1

else

trueCount),

Action<int> (fun x -> System.Threading.Interlocked.Add(&trueLength,x) |> ignore) ) |> ignore

let res1 = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked trueLength

let res2 = Array.zeroCreateUnchecked (inputLength - trueLength)

let mutable iTrue = 0

let mutable iFalse = 0

for i = 0 to isTrue.Length-1 do

if isTrue.[i] then

res1.[iTrue] <- array.[i]

iTrue <- iTrue + 1

else

res2.[iFalse] <- array.[i]

iFalse <- iFalse + 1

res1, res2

In this case, each thread has its’ own accumulator value, keeping track of their own trueCount. So they are free to increment it without locking.

As threads finish, they then do a locked add, adding their own personal trueCount to the final result stored in trueLength. This locked add only happens

NumThreads times, instead of array.Length times, so causes no terrible performance penalty. The final result is about 30% faster with no memory use penalty.

Performance test results of Array.Parallel.partition with predicate (fun x -> x % 2 = 0)

| Method | Length | Median | StdDev | Scaled | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Bytes Allocated/Op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 1000 | 21.8514 us | 0.5300 us | 1.00 | 0.16 | - | - | 3,471.77 |

| New | 1000 | 20.5297 us | 0.8840 us | 0.94 | 0.17 | - | - | 3,489.75 |

| Original | 10000 | 160.0466 us | 3.1249 us | 1.00 | 1.21 | - | - | 28,955.03 |

| New | 10000 | 118.1885 us | 2.8572 us | 0.74 | 1.20 | - | - | 28,666.02 |

| Original | 100000 | 1,282.9827 us | 7.3705 us | 1.00 | - | - | 10.17 | 211,334.08 |

| New | 100000 | 917.0063 us | 17.4501 us | 0.71 | - | - | 7.27 | 151,441.53 |

| Original | 1000000 | 12,467.9427 us | 728.8799 us | 1.00 | - | - | 65.99 | 2,353,833.73 |

| New | 1000000 | 9,700.7108 us | 990.4339 us | 0.78 | - | - | 65.24 | 2,309,151.64 |

| Original | 10000000 | 125,043.1745 us | 1,753.3497 us | 1.00 | - | - | 35.28 | 29,670,713.02 |

| New | 10000000 | 86,908.7271 us | 1,472.4448 us | 0.70 | - | - | 35.53 | 29,909,345.33 |

Recursion is slower … sometimes

Sometimes a recursive implementation will be a substantive speed hit. While the F# compiler is very good at tail recursion optimization, turning most recursive functions into nice loops, there can still be a small to medium performance penalty in some cases. For example, Array.compareWith got about 20% faster when converted from this recursive implementation to while loops:

let inline compareWith (comparer:'T -> 'T -> int) (array1: 'T[]) (array2: 'T[]) =

checkNonNull "array1" array1

checkNonNull "array2" array2

let length1 = array1.Length

let length2 = array2.Length

let minLength = Operators.min length1 length2

let rec loop index =

if index = minLength then

if length1 = length2 then 0

elif length1 < length2 then -1

else 1

else

let result = comparer array1.[index] array2.[index]

if result <> 0 then result else

loop (index+1)

loop 0

It took some care to realize this performance improvement, early attempts were actually worse. So keep in mind that testing and IL inspection will be necessary to know for sure if a recursive implementation is a problem. It often is not.

Notes on Benchmarking

Benchmarking managed code isn’t easy. As well as dealing with non deterministic hardware and operating systems just like you do with C/C++, you also add the complication of the JIT, the runtime, and garbage collection. All of these things can cause code to run faster one moment, and slower the next. Especially when looking for marginal gains you can easily fool yourself into thinking you have made progress when you have actually regressed, or vice versa. Also you may have achieved a slight runtime improvement for your function, but generated more garbage that has to be collected, leading to a net loss. Or maybe you thrashed the L1 cache with your new algorithm such that the next function goes slower, when run in the context of a full program. These can be hard to identify in a benchmark. This is why I cringe a bit when I see people say “you can optimize it later when you identify that it is a bottleneck”. Identifying bottlenecks can be hard. If you see easy ways to avoid pointer hopping or creating garbage, take them.

I used the BenchmarkDotNet library which helps solve some, but not all, of these challenges. It will automatically warm up the JIT for you, figure out how many trials need to run for each test to get good data, and report on memory usage and GC events (though this feature has some bugs, so be careful). It also spits out nice reports on the results in HTML, CSV, and Markdown formats. The Markdown format is very handy as you can paste it into your Pull Requests. You can see a sample stub that I used here.

You can do this too

If you are interested in improving the quality or performance of software in the world, consider doing something about it. You do not need to be highly skilled or experienced. I am just an average web developer by day, not a language architect or assembler expert or anything. You just need some patience. Learning how a given project’s repository and build process works is often the hardest part. Ask questions of the community, don’t worry about seeming dumb. You will get less dumb every time you ask a dumb question. Pick your favorite open source language or library, make it better. Code bases are huge and even those written by grey beard wizards will have mistakes and bottlenecks that you can find and fix. If the code base is way above your head, start with improving documentation or error messages or other important but not so glamorous work. It is always highly appreciated, and can be a way to familiarize yourself with the project and endear yourself to the other team members. Plus it also makes the world a better place.

What does this mean for FSharp

The net effect of all of this for F# programs out there will vary considerably. For the changes I’ve been working on you need to be making use of arrays (you should! Learn about cache misses). There are PRs from other people for performance improvements in other areas too, which is great to see. If you are using arrays and using the core library Array module, things will just go faster. Whether it makes a substantive difference just depends on your use case. For fun I put together a toy example that hits a lot of the key functions that have been sped up, and compared the current 4.4.0 Core lib against what will hopefully all get merged into 4.4.1:

(* Init,create and map faster due to array bounds check elision *)

let array1 = Array.init TEN_MILLION (fun i -> i)

let array2 = Array.create TEN_MILLION 5

let added = Array.map2 (fun x y -> x+y) array1 array2

(* Rev faster due to array bounds elision and micro optimizations *)

let backwards = added |> Array.rev

(* AverageBy is much faster as it now no longer just calls into Seq.AverageBy *)

let average = backwards |> Array.averageBy (fun x-> (float)x)

(* Use aggregating Parallel.For loop *)

let greaterThan400 = backwards

|> Array.Parallel.choose (fun x -> match x with

| x when x > 400 -> Some x

| _ -> None )

(* Partition faster and uses less memory due to new algorithm *)

let (even,odd) = greaterThan400 |> Array.partition (fun x -> x % 2 = 0)

(* Filter faster due to using preallocated array instead of List<T> *)

let filtered = even |> Array.filter(fun x -> x % 4 = 0)

Results

Host Process Environment Information:

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.9.8.0

OS=Microsoft Windows NT 6.2.9200.0

Processor=Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4712HQ CPU 2.30GHz, ProcessorCount=8

Frequency=2240908 ticks, Resolution=446.2477 ns, Timer=TSC

CLR=MS.NET 4.0.30319.42000, Arch=64-bit RELEASE [RyuJIT]

GC=Concurrent Workstation

JitModules=clrjit-v4.6.1590.0

Type=SIMDBenchmark Mode=Throughput Platform=X64

Jit=RyuJit GarbageCollection=Concurrent Workstation

| Method | Length | Median | StdDev | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Bytes Allocated/Op |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | 10 | 3.4036 us | 0.0806 us | 0.07 | 0.00 | - | 852.03 |

| New | 10 | 3.4044 us | 0.3243 us | 0.08 | 0.00 | - | 1,118.24 |

| Old | 1000 | 52.2478 us | 4.7930 us | 2.15 | - | - | 31,762.76 |

| New | 1000 | 41.3602 us | 2.7741 us | 1.37 | - | - | 22,699.78 |

| Old | 100000 | 6,001.7350 us | 286.9376 us | 58.77 | 2.10 | 74.12 | 3,114,798.18 |

| New | 100000 | 3,296.3410 us | 89.5167 us | - | - | 78.91 | 3,254,820.11 |

| Old | 1000000 | 40,985.6462 us | 830.1541 us | 556.34 | - | 211.89 | 30,759,505.83 |

| New | 1000000 | 33,555.2876 us | 3,514.3688 us | 519.70 | - | 229.11 | 29,579,065.56 |

| Old | 10000000 | 405,780.3801 us | 8,032.9328 us | 5,660.00 | - | 227.00 | 333,268,994.49 |

| New | 10000000 | 286,415.5958 us | 7,394.8703 us | 5,049.00 | - | 183.00 | 287,616,350.72 |